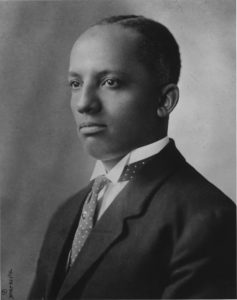

Carter G. Woodson

By Burnis R. Morris

When Carter G. Woodson departed West Virginia in 1903 for the Philippines and other distant datelines, few people other than Woodson himself could have imagined his final destination. He would eventually enjoin millions to follow his lead in promoting African Americans’ contributions in history; however, the scholarly people in Washington, where he settled in 1909, laughed at him and predicted failure.

One of the great mysteries of that time – and probably since – is how this interloper from a region of the country unknown as a producer of black leadership and scholarship rose to the helm of the Modern Black History Movement. Few people knew Woodson had already groomed himself in Appalachia for a war he would declare and “prosecute” (a word he used often). This part of Woodson’s story, 1875 to 1903, is not a typical rags-to-riches narrative. A former coal miner and son of former slaves, he confronted enormous obstacles, believing education was the great equalizer. He was not motivated by aspirations for wealth.

Woodson did not accommodate voyeurs with an autobiography, but he left behind archived documents and comments tucked away, sometimes as digressions, in newspaper articles involving other topics – all of them sources for reconstruction of this period. The early years are the period Woodson followers know least and often misunderstand. A Chicago Defender columnist, for example, suggested Woodson was illiterate as a young adult. Howard University professor Kelly Miller, one of the scholarly people Woodson identified as predicting his failure, argued that Woodson arrived to lead the rescue of his race late in life and compared his self-help philosophy to Marcus Garvey’s – only distinguishing them by saying Woodson’s views were moderated by his Anglo-Saxon education.

Indeed, Woodson was late to the scene, just shy of 40 when he founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. However, his Anglo-Saxon education (presumably reference to Woodson’s training at prestigious institutions) was undeniably an asset, but it did not form the core of his beliefs. Woodson said he had been taught the same theories of black inferiority as other students, but he handled the misinformation better than most because he had been well-grounded.

Woodson said his parents, James and Anne Eliza, first moved into the area on the Ohio River that became Huntington, West Virginia, in 1870. One Woodson biographer suggested they walked 300 miles from Virginia to the site, where James Woodson was one of several former slaves who helped complete the Chesapeake and Ohio railroad. Woodson also said his father helped build Huntington. The family moved back to Virginia in 1874, it has been speculated, to escape unsanitary conditions in Huntington and health risks to their four living children, having already lost two children to whooping cough.

Carter Godwin Woodson was born on December 19, 1875, near New Canton, in Buckingham County. Carter, one of nine children, said he often left the dinner table hungry and sought food in nearby woods. After he went to bed on Saturday nights, his mother washed the clothing he had been wearing so he could don clean clothes to church on Sundays.

James Woodson, a Civil War veteran who learned carpentry from his father, earned money laying foundations for homes. Carter worked the family’s six-acre farm, which was located on mostly poor land, but it produced vegetables for the large family. Carter said his father was illiterate and intelligent, and he bestowed guiding principles about life on him. He did not hire out his children to supplement family income, and when he had dealings at others’ homes, including white residents’, he avoided going to their back doors. James Woodson’s principles put blacks and whites on equal footing, and that often meant hardship, but Carter said his father “believed that such a life was more honorable than to serve one as a menial.”

At 12 years old, Woodson read a story in a McGuffey Reader involving two boys, George Jones and Charles Bullard, with moral, religious overtones. The Bullard character studied his lessons before going out to play games, which he played well, and he was popular, went off to college, became class valedictorian and had great success in life. Jones, on the other hand, did not study and played poorly; he was not well liked and was a failure. After he finished reading the story, Woodson decided “I’m going to be Charles Bullard” and set his sights on college.

His school had a five-month term each year, but Woodson usually attended only on days of rain and snow, when he was not needed to work the farm. He was an excellent student when he showed up and often completed assignments early. With nothing else to do he became a cut-up in class, sometimes prompting whippings by school officials, then, another at home by his father.

By the few accounts available, Woodson was an obedient, dutiful son, possibly his mother’s favorite child. In the family home, he heard Mrs. Woodson express dislike for George Washington because she and other slaves had seen his statue in Richmond when they were being auctioned and interpreted his hand gesture (pointing south) as support for Southern slavery. Carter, nonetheless, praised the work of the first president, arguing he helped create a system of government that ultimately made emancipation possible.

Life was not all somber, however, and Woodson did find humor amid hardships in Buckingham County, even on race relations. He recalled attending the memorial service of a polygamous white Baptist preacher and singing “Shall We Meet Beyond the River?” He wondered whether the preacher would be meeting “his white wife or colored paramour on the other side.”

The Woodson family returned to Huntington in 1893 on the recommendation of Robert, Carter’s older brother, who reported on the prosperity that awaited them. Before joining the family, Carter said he and Robert completed jobs building the railroad from Thurmond to Loup Creek and working in the coalfields at Nuttallburg, in Fayette County, West Virginia. Carter said he had a six-year apprenticeship in the coal mines.

At least two people Woodson met in the mines left indelible impressions on him: Oliver Jones, a black Civil War veteran who ran a tearoom, where other black miners gathered after work; and a white miner whom Woodson did not name.

In Jones, Woodson found the embodiment of a well-educated man, the antithesis of the college-educated people Woodson described as mis-educated. Jones was an illiterate who collected books and subscribed to many newspapers. Woodson said Jones learned as friends read to him, and he persuaded Woodson to read to the other illiterate miners, as he had been doing for his father. This arrangement allowed Woodson to learn much about the outside world that influenced his thinking and extended his appreciation for illiterates, whom he held in high regard the remainder of his life.

The white coal miner, on the other hand, was the symbol of what Woodson disliked about religion. The miner, a devout Episcopalian, bragged about his participation in the attacks on four blacks in Clifton Forge, Virginia, and their lynching in 1892, causing Woodson to question the legitimacy of religion. Woodson judged this miner as a representative of the people who used religion to support the slavery system, and Woodson’s reaction to him helps explain Woodson’s relentless attacks in the 1930s on black church leaders with close ties to institutions that promoted segregation, such as the YMCA. He considered segregation an evil remnant of slavery and called it unchristian.

Woodson enrolled in 1895 at Huntington’s all-black Douglass High School and was frequently absent because he was off working, but he studied Virgil and Caesar on his own. He tested well and received a diploma after about a year of a two-year program in 1896, in a graduating class of two. Woodson then studied briefly at Berea College in Kentucky and at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania before moving to Fayette County, West Virginia, and teaching high school in Winona. Despite misgivings about churches run by the wrong people, Woodson remained a Christian, serving as a Sunday schoolteacher and president of the board of deacons of the First Baptist Church in Winona.

In 1900 Carter H. Barnett, a Woodson first cousin, was fired as principal of Douglass High School because of his politics. The West Virginia Spokesman, a newspaper Barnett edited, supported independent black politics, rather than party lines, as did Woodson when he discussed politics in Washington, and the cousins shared a bold, combative style. Barnett promoted his own slate of local candidates, which included Woodson’s brother Robert. The episode played out over several weeks in The Huntington Advertiser, a white newspaper, and Woodson was hired to replace Barnett as principal that summer.

While principal, Woodson earned a West Virginia teaching certificate with an average score of 91 and gained recognition in the local press when he honored William McKinley in a special service at Douglass following the president’s assassination in 1901. He sketched McKinley’s biography and suggested singing “Nearer My God to Thee.” His name also made the newspaper when he officiated at high school commencements, including his sister Betsy’s. In private life, Woodson continued to read aloud to his father and was said to bring breakfast to him at his railroad job on Sundays.

Woodson finally completed the two-year, B.L degree at Berea in 1903. He saw Booker T. Washington for the first time, in Lexington, Kentucky, that year and was impressed by Washington’s oratory and, was still spellbound three decades later when he wrote about the speech. Washington, often criticized for accommodating white racism and preaching industrial education, joked about how well blacks would serve whites – even in hell. Woodson said Washington urged his audience to become scientifically trained in order to serve more efficiently.

In the meantime, Woodson was off to the Philippines as a teacher and supervisor. He sailed on a liner called Korea, in driving rain from San Francisco on November 18, 1903. After his arrival, Woodson learned about mistakes made in Filipino education, lessons he noted for making education more relevant back home.

Burnis R. Morris is the Carter G. Woodson Professor of Journalism and Mass Communications at Marshall University.