This article first appeared in BlackArtInAmerica.com

“The HBCUs have not been given the credit they are due. When nobody else was out there championing these [Black] artists, HBCUs were there, claiming them, showcasing them, putting them up on walls, teaching about them” — Artist and art historian, David C. Driskell, from the HBO documentary, “Black Art: In the Absence of Light”

Too often the history of Black people is centered on the actions of White people and the chronicling of African-American art history is no exception. As we witness record breaking sales for Jean-Michel Basquiat’s paintings, and African-American and African artists selling works for six figures and being acquired by museums, we must remember that the foundation for these achievements are Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) not White art collectors, New York galleries, or the major auction houses.

The oldest HBCU in the United States is Cheyney University, founded in 1837 in Pennsylvania by Quaker philanthropist Richard Humphreys. In 1865, Congress enacted the Freedmen’s Bureau, which led to the federal chartering of institutions of higher education for newly emancipated Blacks. The early focus of HBCUs was on training Black people to become teachers, farmers, and ministers.

Until the 1960s, colleges, art schools and galleries in the United States routinely rejected African-American applicants solely on the basis of their race. Legal segregation forced HBCUs to create opportunities for Black artists to be trained as well as to have their work exhibited and acquired. In the 2021 HBO documentary, “Black Art: In the Absence of Light,” Harvard University professor, Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, underscores the importance of HBCUs to art history, stating:

“Without the work of Historically Black Colleges and Universities we wouldn’t have a repository of African-American art that we can draw on.”

“Black Art: In the Absence of Light” was inspired by David C. Driskell’s (1931-2020) groundbreaking 1976 exhibition, “Two Centuries of Black American Art.” Driskell’s exhibition was pivotal to correcting the narrative of American art history. The exhibition exposed the nation to several generations of African-American artists who had been systematically excluded from the American art canon. Moreover, Driskell’s exhibition allowed a younger generation of African-Americans to envision themselves as artists, curators, art historians and museum directors. Driskell was a graduate of Howard University, an HBCU.

To be accurate, there were White Freedmen’s Bureau officials, White philanthropists and White art patrons present in both the establishment of HBCUs and in the history of African-American art. These participants had an array of social, religious, and political agendas that are beyond the scope of this article. It suffices to say that, generally, their views of Black people and Black artists were, at best, paternalistic.

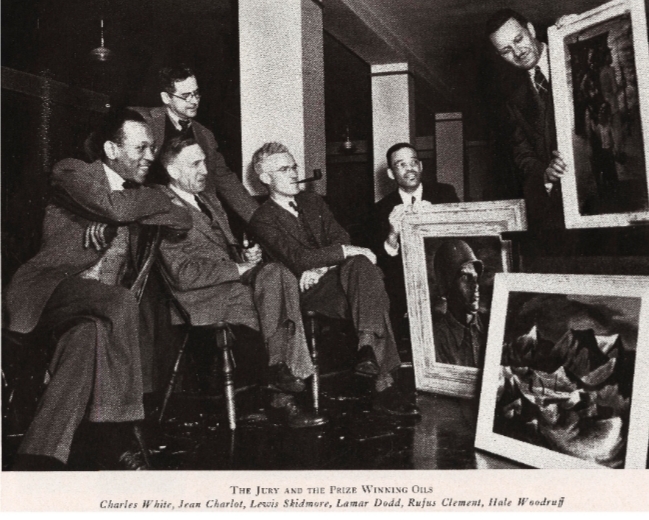

What is relevant to this discussion is that the HBCUs used their limited resources to train Black artists; acquire work created by artists of African descent; and provide Black artists with professional guidance and support. HBCUs were the first patrons of African-American art…