The Origins of Black History Month

WRITTEN BY Daryl Michael Scott | ASALH Former National President

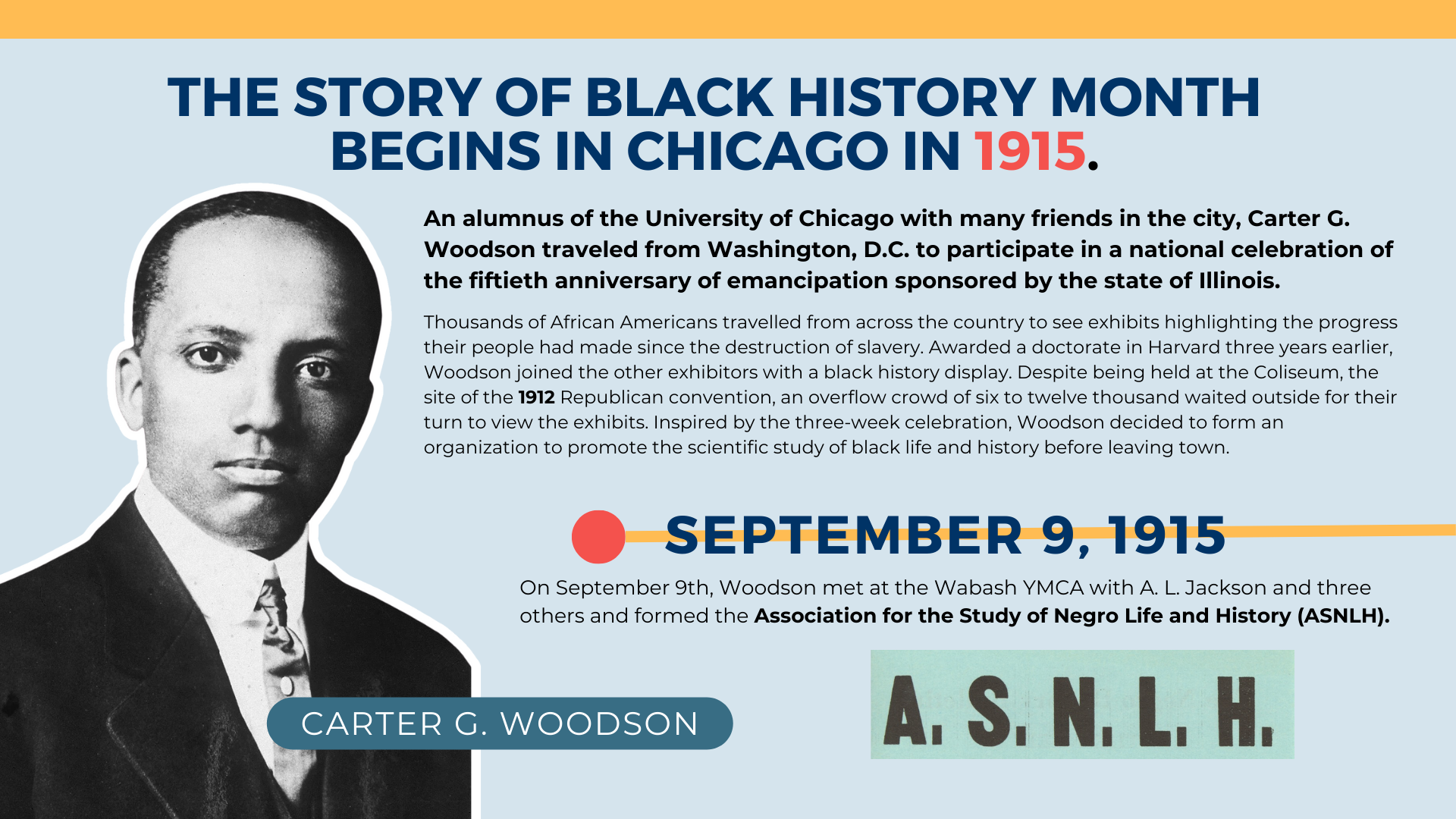

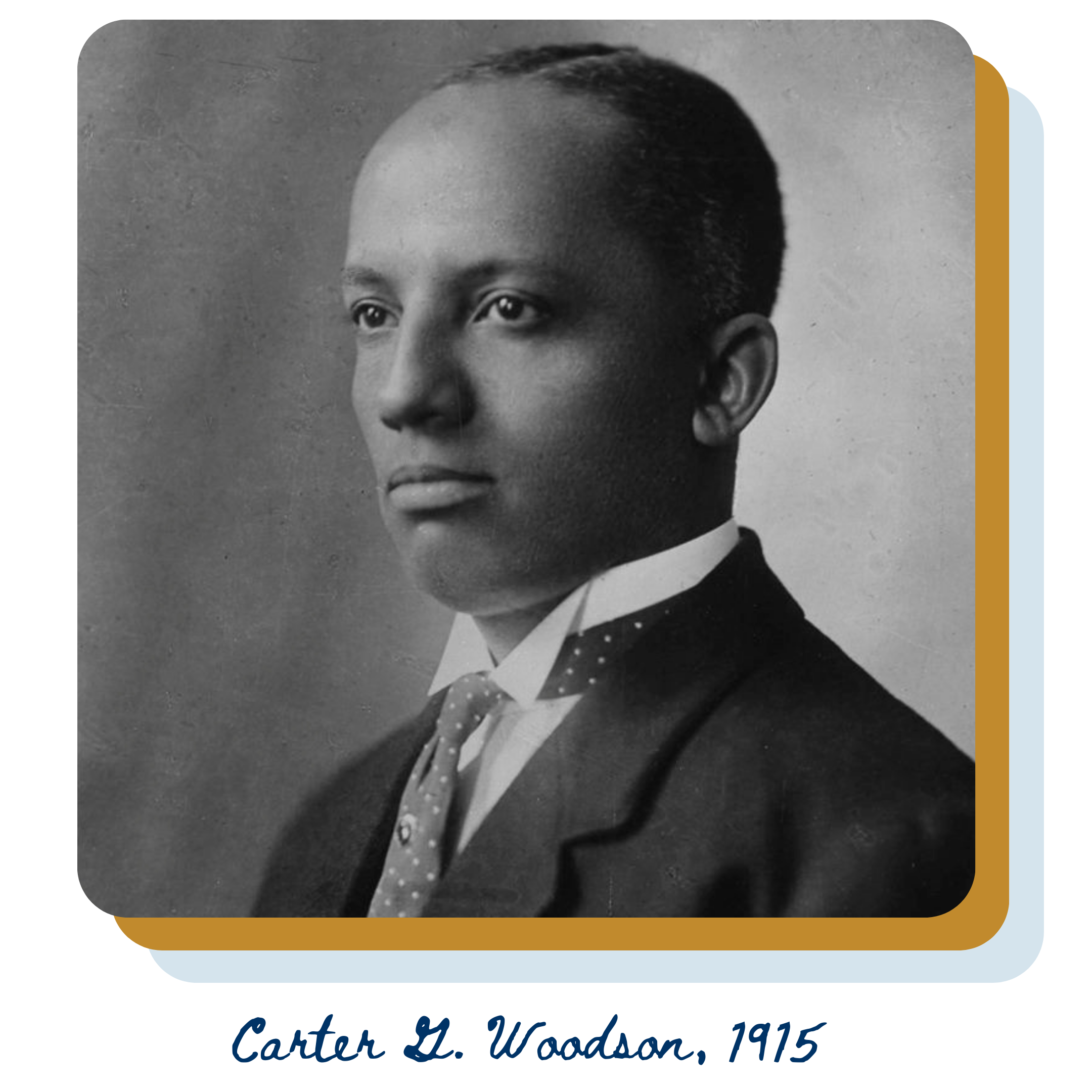

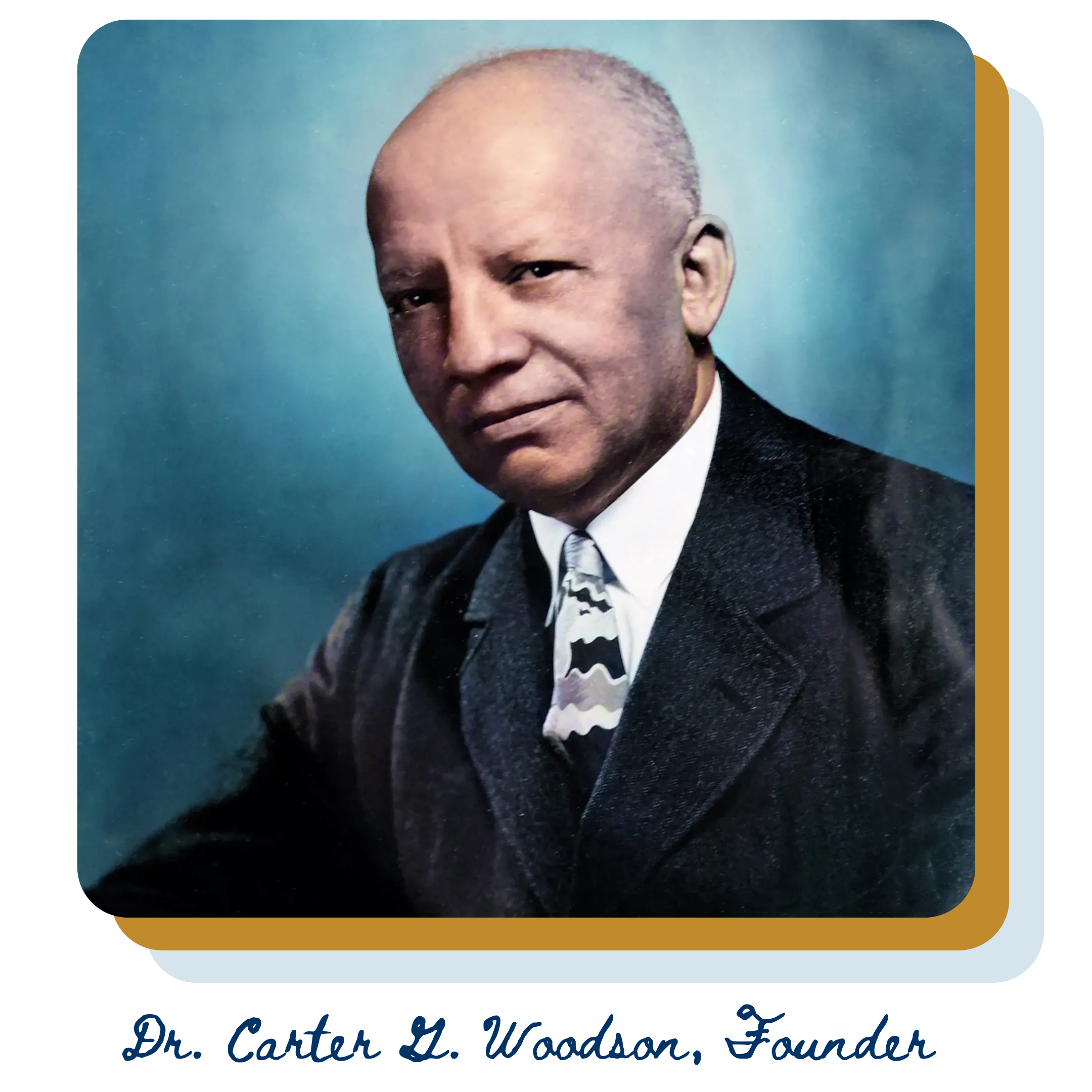

The story of Black History Month begins in Chicago during the summer of 1915. An alumnus of the University of Chicago with many friends in the city, Carter G. Woodson traveled from Washington, D.C. to participate in a national celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of emancipation sponsored by the state of Illinois. Thousands of African Americans travelled from across the country to see exhibits highlighting the progress their people had made since the destruction of slavery. Awarded a doctorate in Harvard three years earlier, Woodson joined the other exhibitors with a black history display. Despite being held at the Coliseum, the site of the 1912 Republican convention, an overflow crowd of six to twelve thousand waited outside for their turn to view the exhibits. Inspired by the three-week celebration, Woodson decided to form an organization to promote the scientific study of black life and history before leaving town. On September 9th, Woodson met at the Wabash YMCA with A. L. Jackson and three others and formed the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH).

What is Black History Month?

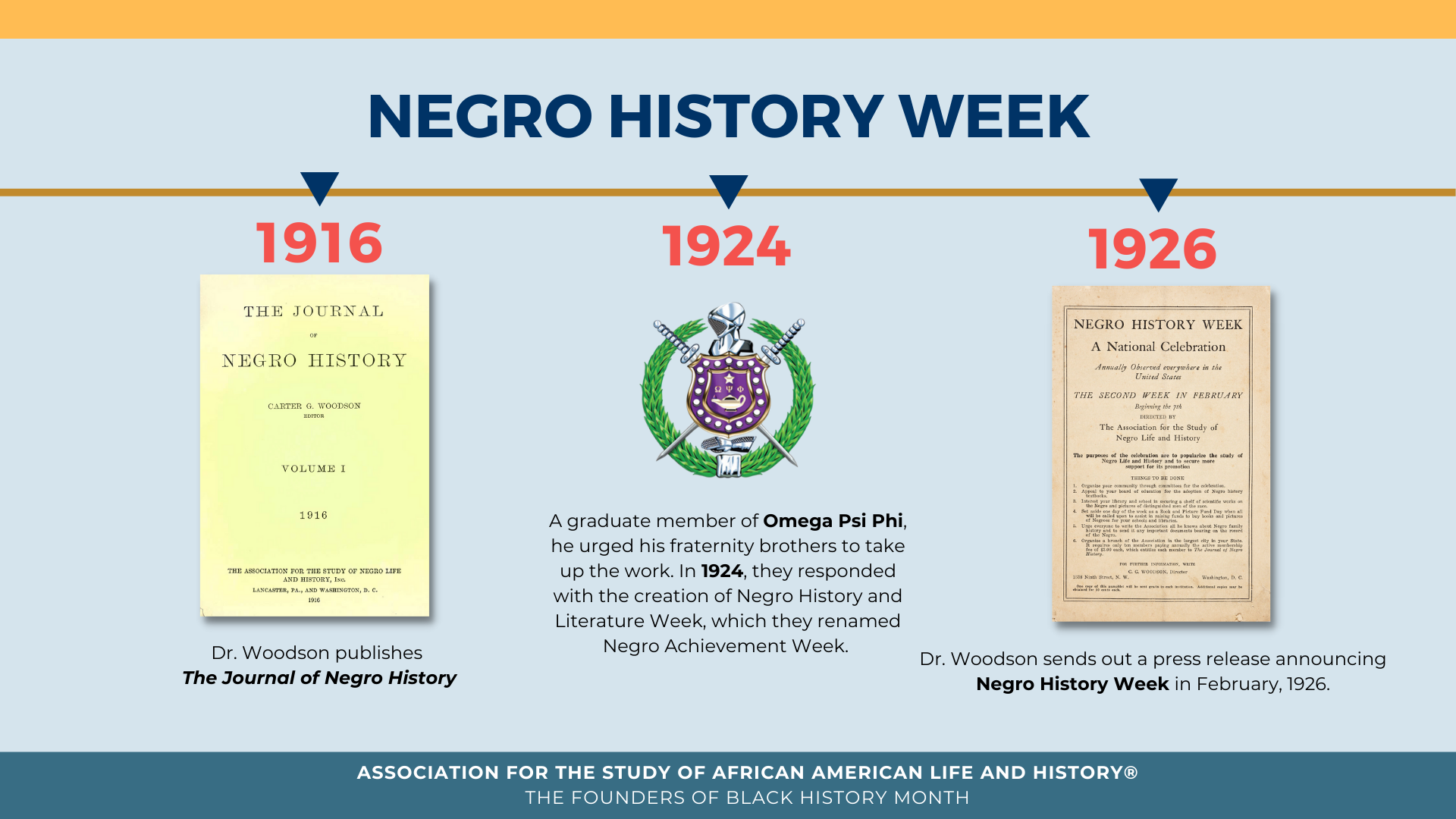

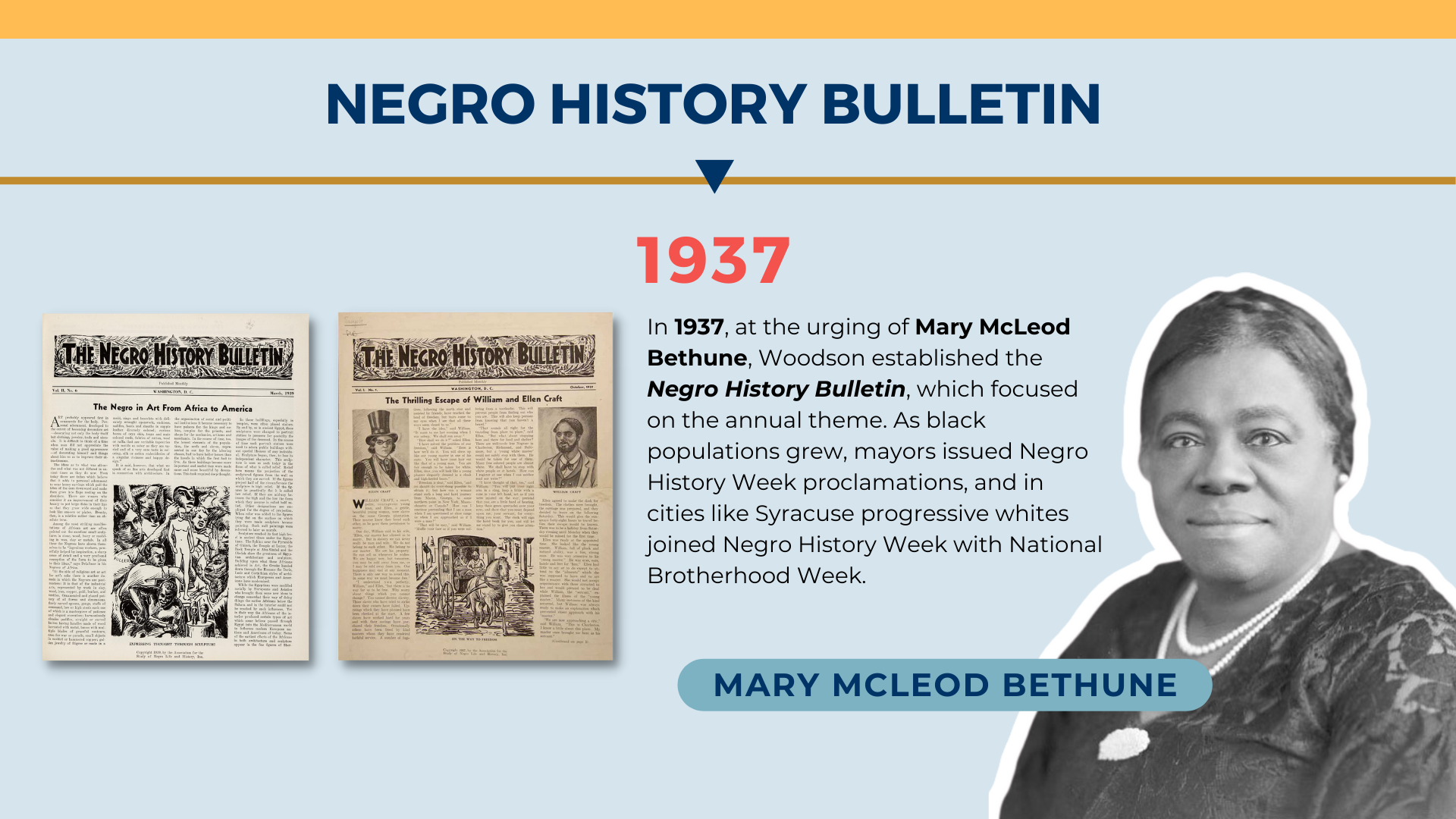

Black History Month is an annually observed month-long celebration of African American life, History, and culture. Founded by Dr. Carter G. Woodson in February 1926, what was Formerly known as Negro History Week became a month-long celebration as a way to promote, research, preserve, interpret, and disseminate information about Black life, History, and culture to the global community.

Why February?

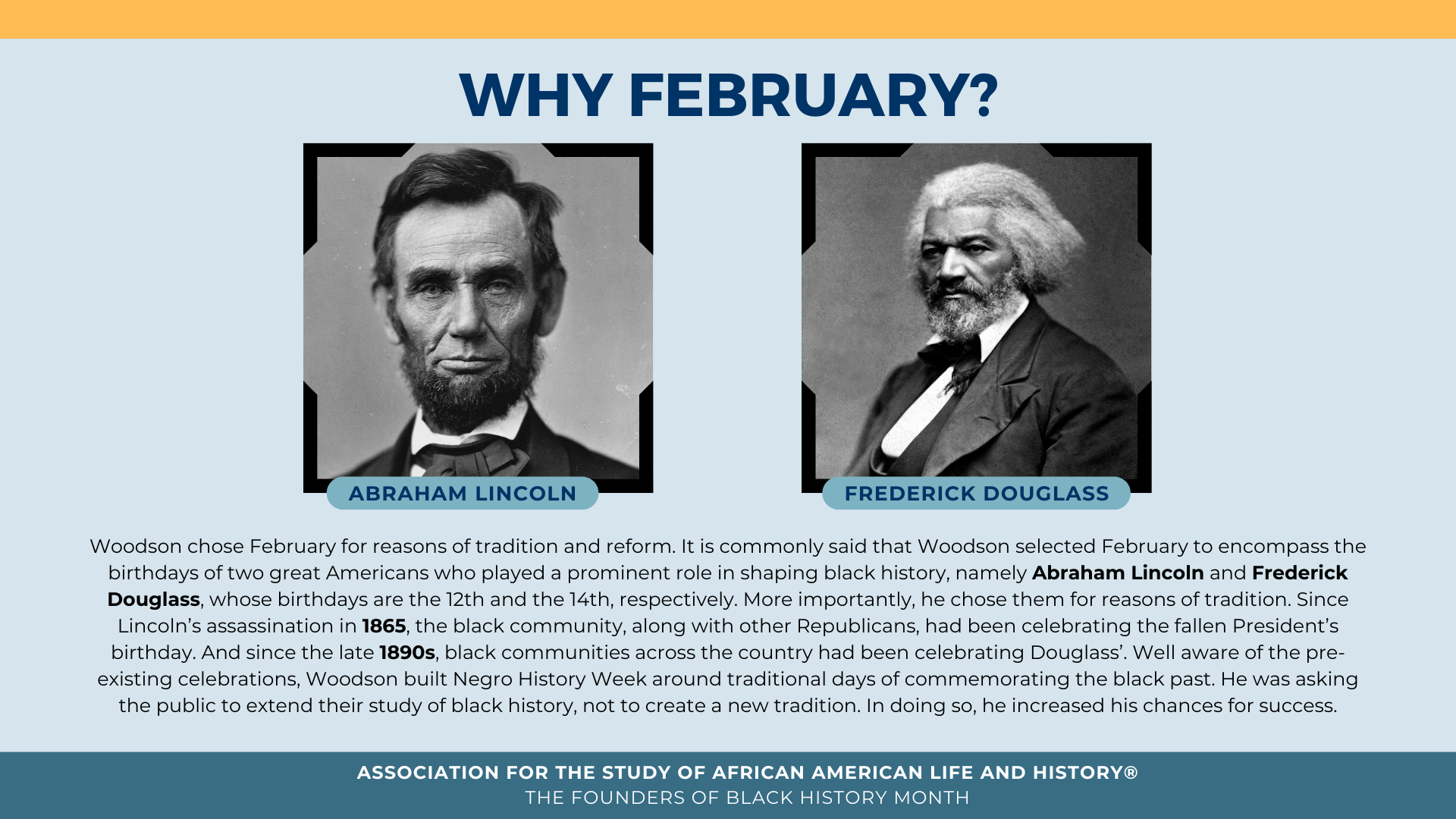

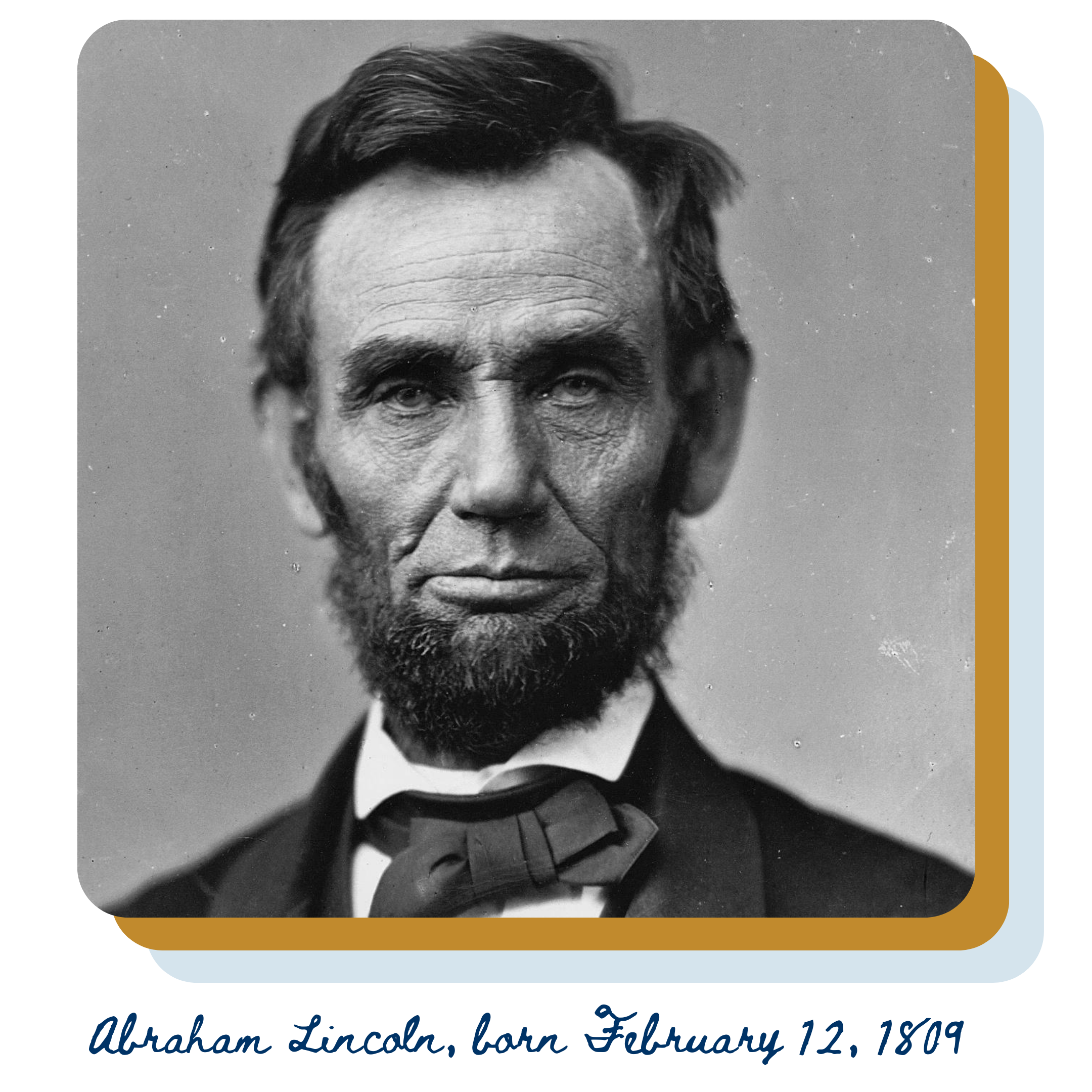

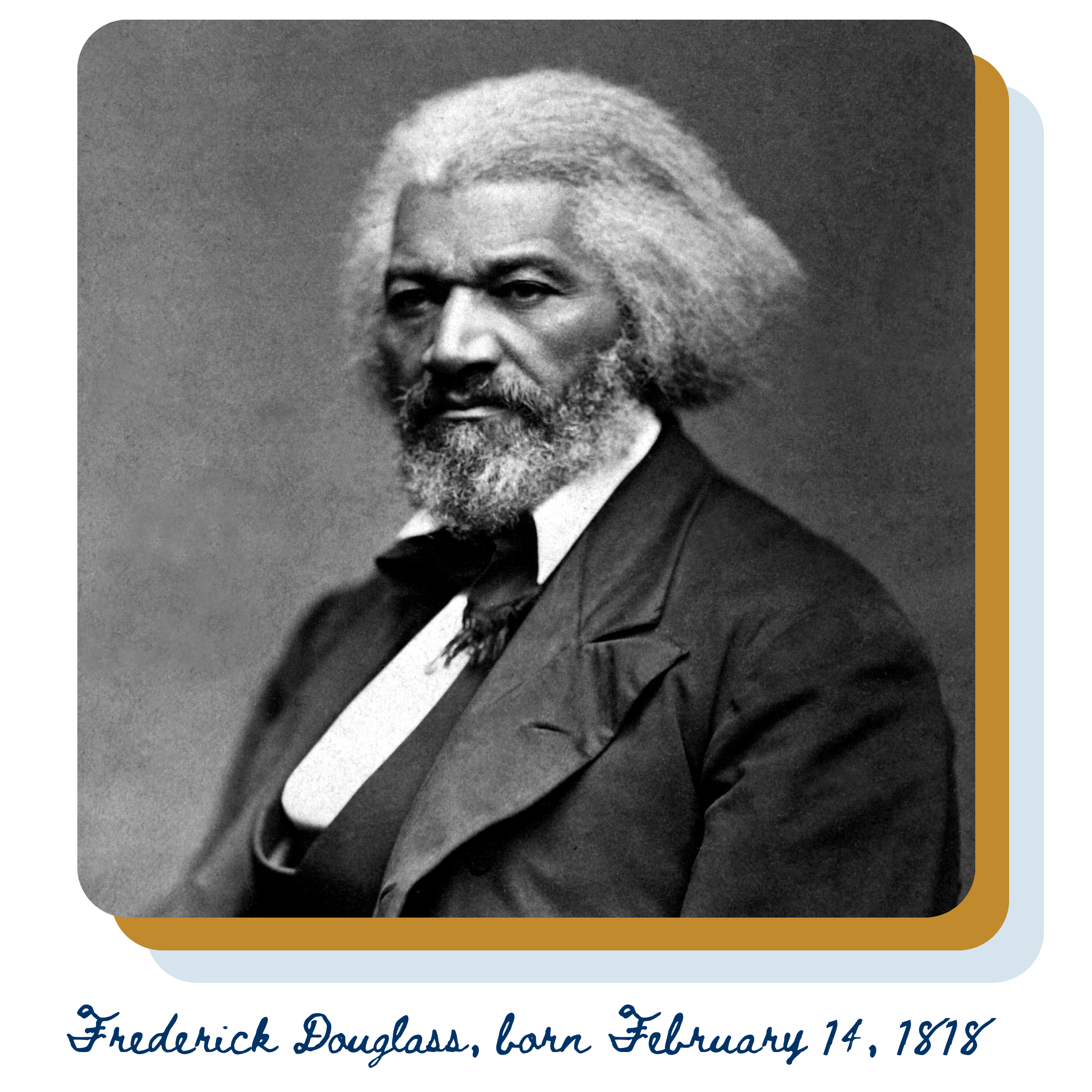

Each year the question is asked: Why does Black History Month occur in February? The relevance of February goes back to 1926, when ASALH’s founder Dr. Carter G. Woodson first established “Negro History Week” during the second week of February. And why that week? Because it encompasses the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass—both men being great American symbols of freedom.

Woodson chose February for reasons of tradition and reform. It is commonly said that Woodson selected February to encompass the birthdays of two great Americans who played a prominent role in shaping black history, namely Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, whose birthdays are the 12th and the 14th, respectively. More importantly, he chose them for reasons of tradition. Since Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, the black community, along with other Republicans, had been celebrating the fallen President’s birthday. And since the late 1890s, black communities across the country had been celebrating Douglass’. Well aware of the pre-existing celebrations, Woodson built Negro History Week around traditional days of commemorating the black past. He was asking the public to extend their study of black history, not to create a new tradition. In doing so, he increased his chances for success.

However, Woodson never confined Negro History to a week. His life’s work and the mission of ASALH since its founding in 1915 represent a living testimony to the year-round and year-after-year study of African American history.

How to Celebrate Black History Month

Explore Black history.

Learn about Black history by exploring your local community, reading books by Black authors, and visiting Black or African-American history museums.

Read books or stories written by Black authors.

Explore a captivating collection of books by talented Black writers on ASALH’s Author’s Bookshelf. Discover unique perspectives and rich narratives reflecting diverse experiences and cultural histories.

Support Black-owned businesses.

By choosing to shop from Black-owned businesses, you contribute to greater diversity in the marketplace and help create opportunities for underrepresented communities. Consider exploring local shops, restaurants, and services to uplift these valuable businesses.

Learn about Black leaders.

Learn about influential Black leaders who have shaped history and continue to inspire. Follow ASALH on social media that highlights the legacies of Black leaders through its Black Facts posts, which celebrate the achievements and impact of these pivotal figures.

Watch films and documentaries created by Black filmmakers.

Explore an array of films and documentaries by talented Black filmmakers on ASALH TV. Discover diverse narratives that celebrate the rich experiences, cultures, and histories of the Black community. Be sure to check out highlights from previous ASALH Film Festivals, showcasing powerful stories and perspectives.

Organize educational events.

Plan interactive history lessons, social activism projects, and other activities. Social Justice at ASALH focuses on the community, bringing practical knowledge and theories learned through the lived experience of activists and oppressed groups that are often overlooked or discounted inside the academy.

Commit to beyond February.

Make a strategic commitment to Black History Month, and don’t limit your efforts to just February. Consider making a monthly donation to ASALH.

Submit Your Black History Month Event

Only ASALH members can submit their events for consideration. To join ASALH and make an impact on Black History, click here.

Why Black History Month!

As the national president of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, it is my honor to bring greetings on behalf of ASALH during Black History Month. Each year the question is asked: Why does Black History Month occur in February? The relevance of February goes back to 1926, when ASALH’s founder Dr. Carter G. Woodson first established “Negro History Week” during the second week of February. And why that week? Because it encompasses the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass—both men being great American symbols of freedom. However, Woodson never confined Negro History to a week. His life’s work and the mission of ASALH since its founding in 1915 represent a living testimony to the year-round and year-after-year study of African American history.

The genius of Dr. Woodson could be seen in his prolific scholarship and in his mentorship of younger scholars. His genius could also be seen in innovative popular programming, such as Negro History Week, for African Americans of all ages and all walks of life. The week provided a special time for us to collectively celebrate our racial pride as well as collectively assess white America’s commitment to its professed ideals of freedom. Black teachers in segregated public elementary and secondary schools engaged their students in an array of festivities—plays, pageants, reciting of speeches, essay contests, concerts, and other events. At the opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC, in 2016, the late Congressman John Lewis shared fond memories of his boyhood school experiences during Negro History Week in rural Alabama. Negro History Week included yet another tradition—an annual fundraising banquet attended by ASALH’s adult members, who listened to inspiring speeches on the role of knowledge in the ongoing struggle for racial equality. It is no wonder that the NAACP conferred its highest medal, the Spingarn Medal, on Carter G. Woodson in 1926 after he launched Negro History Week that very same year. Today in the twenty-first century, ASALH remains faithful to Woodson’s legacy of excellent scholarship and innovative programming.

We also recognize that during the mid-1960s, and especially when college students demanded courses on African Americans and led protests demanding Black Studies Departments, there were calls for extending Negro History week into a monthlong celebration from such groups as the Pan-American/Pan-African Association in Washington DC and students at Kent State University in Ohio, and from local communities throughout America. ASALH, however, sought recognition from the federal government, in the belief that it was important for our nation to set aside the month of February in official observance of African Americans’ contributions to the history of the United States and world. The first official observance came in February 1976, from President Gerald Ford whose words established Black History Month in eloquent homage to Woodson and ASALH. He proclaimed: “IN THE Bicentennial year of our Independence, we can review with admiration the impressive contributions of black Americans to our national life….[T]o help highlight these achievements, Dr. Carter G. Woodson founded the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History. We are grateful to him today for his initiative, and we are richer for the work of his organization.”

Ten years later in 1986, which was also the first year of the celebration of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birthday as a national holiday, the U.S. Congress, in a joint resolution of the House and Senate, designated the month of February as “National Black History Month.” The resolution authorized and requested President Ronald Reagan to issue a proclamation in observance. In 1986, the Presidential Proclamation 5443 noted that “the foremost purpose of Black History Month is to make all Americans aware of this struggle for freedom and equal opportunity.”

Thus, let us think of Black History Month the way our nation honors its greatest moments and greatest people. Let us appreciate Black History Month in a similar way—as when our government sets aside a month or day, thereby giving it a special meaning for all Americans. No one should think that Black History is confined to the month of February, when evidence to the contrary appears everywhere and in every month. Thanks to the pioneering work of Woodson and ASALH, information on the contributions of persons of African descent to our nation and world is currently taught in universities and in many K-12 schools. Black History is featured in television documentaries and in local and national museums. It is conveyed through literature, the visual arts, and music. The great lives and material culture of Black History can be seen in national park sites and in the preservation of historic homes, buildings, and even cemeteries. Black History Month is not a token. It is a special tribute—a time of acknowledgement, of reflection, and inspiration—that comes to life in real and ongoing activities throughout the year, just as the work of ASALH has for 106 years steadily asserted both racial pride and the centrality of race and the black experience to the American narrative and heritage.

The history of the United States is certainly taught and conveyed all year long, but its greatest symbolic celebration occurs on one-day, the Fourth of July. Black History Month, too, is a powerful symbolic celebration. And symbols always stand for something bigger—in our case, the important role of Black History in pursuit of racial justice and equality. We invite you to partake of ASALH’s virtual Black History Month Festival. For information, see https://asalh.org/festival/schedule-of-events/. We’ll be talking a lot about the Black History Theme for 2021—The Black Family: Representation, Identity, and Diversity. See my announcement of the 2021 theme on asalh.org. ASALH will explore The Black Family from a multiplicity of perspectives, HBCU vocal performances, and enlightening discussions during the festival and, to be sure, All Year Long!

Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham

2021 ASALH National President