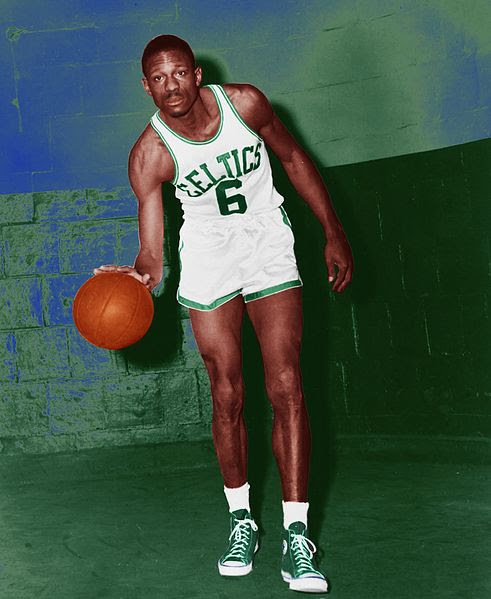

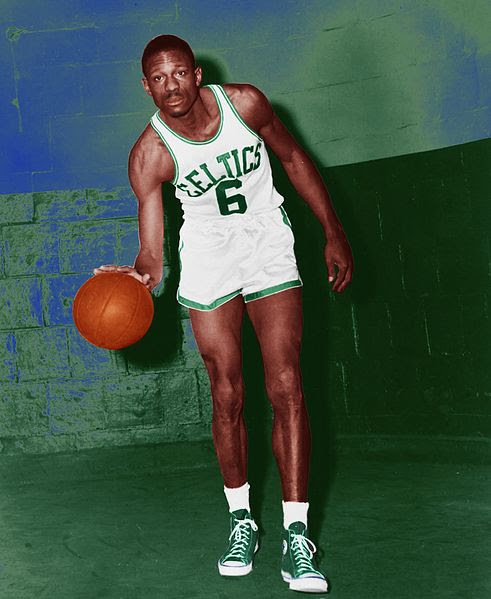

The Association for the Study of African American Life and History mourns the death of William Felton Russell. Russell is the winningest professional athlete of all time in team sports. He was the centerpiece of the Boston Celtics dynasty which claimed 11 NBA titles in 13 years, and one with him as player-coach, to become the first Black coach to win an NBA championship. He was a 12-time all-star and 5-time MVP, served as a General Manager of the NBA’s Seattle Supersonics, and led the University of San Francisco to the 1956 and 1957 NCAA titles. He was captain of the 1956 gold-medal winning U.S. Olympics team. But all of that alone, does not address his full impact and significance on sports and society. To fully understand his importance, his life must be framed in the context of his times. Perhaps in 2011, when he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama was the full measure of his contributions revealed to younger generations of Americans, who were not yet born when he retired as a basketball player in 1969.

The Association for the Study of African American Life and History mourns the death of William Felton Russell. Russell is the winningest professional athlete of all time in team sports. He was the centerpiece of the Boston Celtics dynasty which claimed 11 NBA titles in 13 years, and one with him as player-coach, to become the first Black coach to win an NBA championship. He was a 12-time all-star and 5-time MVP, served as a General Manager of the NBA’s Seattle Supersonics, and led the University of San Francisco to the 1956 and 1957 NCAA titles. He was captain of the 1956 gold-medal winning U.S. Olympics team. But all of that alone, does not address his full impact and significance on sports and society. To fully understand his importance, his life must be framed in the context of his times. Perhaps in 2011, when he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama was the full measure of his contributions revealed to younger generations of Americans, who were not yet born when he retired as a basketball player in 1969.

Russell was born in 1934. That was the year, the Dean of the Howard University School of Law, Charles Hamilton Houston conceived and directed the NAACP’s legal campaign against discrimination and segregation/apartheid. Twenty years later, its legal campaign would culminate in the Brown v. Board of Education decision which ruled apartheid schooling unconstitutional. In the midst of the Great Depression, Bill Russell was born in the rigidly apartheid town of Monroe, Louisiana. There racism and restrictions on Black opportunity were so severe that during WWII his parents migrated to Oakland, California. They were attracted by jobs in the war industry and better schools for Bill and his older brother, the revered writer Charlie L. Russell, Jr. At age 12, after his mother, Katie died, his father dedicated himself to fulfilling his wife’s plea that the boys receive a good education and attend college. Russell later recalled, “Education was a great shining stepladder for Black families in those days…though you could not point to many who climbed on it a long way. Still, it was the only hope we had as long as there was only one Joe Louis.”

Russell’s father, affectionately known as Mister Charlie, taught his sons about the dividends of discipline and hard work. Each day when returning home from his factory job, he instilled confidence in his sons that “we were going to make it.” Other than the support and comfort of his father and brother, Bill retreated into his private world with his prized possession, a library card from the Oakland Public Library where he went every day. One day at age 13, he came across a history book by the slavery apologist, historian U.B. Phillips. Russell was enraged and bewildered by its claim that enslaved Black folk enjoyed a higher standard of living and better life in America than in their “primitive African homeland.” Russell said the Phillips book lit an anger that would remain with him through manhood. From that point forward, Russell explored books that gave a more balanced account of Black people in the West, Africa, and America. This is how he found his first hero, “after my mother,” Henri Christophe, who joined in the slave revolt against the French and became emperor of Haiti. Russell also developed an appreciation for the genre of Black history written and promoted by Carter G. Woodson. He became a lifelong history pundit — always searching, probing, and inquiring for truths about history and the human condition. In his own way, with his own style and inimitable blueprint, Russell strongly identified and aligned himself with the goals of the Civil Rights and Black Power movements.

Russell played high school basketball at McClymonds High School in Oakland, California. He won a basketball scholarship to the University of San Francisco, though he was not among the top three players on his high school team. He recalled, “Only one school was interested in me, so I went there. It was that simple.” But he was self-disciplined and worked hard — 8 to 10 hours a day — to improve his game. He first became nationally known, during his junior and senior years (1955 and 56), while leading the Dons to back-to-back NCAA championships. In those same years, Russell learned of the murder of Emmett Till, the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the rise of Martin Luther King, Jr., and the white South’s “Massive Resistance” to the Brown v. Board decision.

He was drafted by the Celtics in 1956, the same year his high school classmate Frank Robinson became baseball’s Rookie of the Year. He was the only Black member of the team his rookie season. There were only eight NBA teams, and no team had more than two Black players. The racial quota system bothered him and as the Civil Rights Movement gained momentum and his celebrity expanded, Russell surprised the sports establishment by becoming a vocal critic of the NBA’s quota system.

A half-century before styles of natural Black hair in the workplace became a civil rights issue in U.S. Courts, Russell ignored advice to shave his beard. In 1959, an NBA proposal attempted to ban facial hair. At that time only two NBA players wore facial hair, the two best players in the league — Russell and Wilt Chamberlain. He called out racism where he saw and experienced it, especially in Boston which he described as a “flea market of racism. ” It was a position from which he never retreated, drawing a line between the city of Boston — whose citizens protested when he purchased a home in a white neighborhood — and the Celtics. He praised the latter for drafting one of the NBA’s first Black players, Chuck Cooper, and additionally, for breaking the quota system; fielding the first all-Black starting line-up; and for hiring him as the NBA’s first Black coach. Years later when Boston retired his jersey, he demanded that it not take place before Boston fans. Thus, it was done in a small ceremony with former Celtics teammates, organization officials, and close friends at the Boston Garden, hours before a nationally televised game. Russell never forgot what he often endured on the court in Boston, being called “baboon,” “coon,” and “nigger.” Despite the titles for which he was the chief architect, when Boston fans were polled about how the team could increase attendance, Russell recalled, more than half responded: “Have fewer Black guys on the team.”

He wanted to be remembered as more than a basketball player. Therefore, he intentionally did not appear for his induction into the Hall of Fame, nor did he participate in the Boston parade when his team won the NBA title with him as coach and player. He thought that too much attention on his basketball achievements allowed many Boston fans to embrace him as an athlete without having to respect his Blackness and the ill-treatment of his race. To Russell’s credit, they could not be bifurcated. He detested all references to Black athletes as “natural ” because it ignored the practice and intellectual preparation that went into being world-class athletes. Russell observed, “I am coming to the realization that we are accepted as entertainers, but that we are not accepted as people in some places. Negroes are in a fight for their rights -a fight for survival -in a changing world. I am with these Negroes.”

In the early 60s, during the prime of his career Russell defended the teachings of Malcolm X. In 1963, he participated in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, as well as protested de facto apartheid in Boston Public Schools. Though a nationally recognized athlete, he remained an activist, going to Mississippi for an extended stay at the request of Charles Evers, the brother of the martyred NAACP leader Medgar Evers and a leader in his own right, following the 1964 murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Mickey Schwerner. He spoke out against the Vietnam War and defended Muhammad Ali’s refusal to be inducted into the U.S. military as a religious conscientious objector. He supported the Olympic Project for Human Rights that led to the iconic raised Black Power fist protest by Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Olympics. Russell publicly disagreed with Daniel P. Moynihan’s report on the Black family. He maintained it was conceptually flawed and would lead to bad public policy. He spoke out against police brutality, racial profiling, and the unfair sentencing of Black defendants in the criminal justice system. Finally, long before the modern cultural wars, Russell challenged the routine genuflection to the founding fathers who were slaveholders. He did all this during an era without the protections of a players union or collective bargaining agreements.

Russell is in a class of ONE, because of his on-court basketball greatness and his racial justice advocacy and action. He used the bully pulpit of his basketball fame and celebrity to increase awareness of the most important social issues of his lifetime and beyond. His style of protest served as a template for activist Black athletes who would follow in his footsteps. For all of his 88 years, he was a Race Man, a person committed to Black people, of extraordinary size — literally and figuratively.

Al-Tony Gilmore is Distinguished Historian Emeritus of the National Education Association. A Life Member of ASALH, he has served on its Executive Council, as Program Chair, and as a member of the Editorial Board of the Journal of African American History. His book, Bad Nigger: The National Impact of Jack Johnson, was the first scholarly book to explore the intersection of race, sports, and society.