By virtue of the good fortune of the spelling of his last name, Henry Aaron was seemingly destined to be the first name listed in the Official Encyclopedia of Baseball. But at that point all coincidences cease. Based on his extraordinary record of achievement , Aaron is ranked first, or in the top five, of more batting categories than any player in the history of baseball — our national pastime. Hitting a baseball is considered the most difficult skill in all of sports, requiring a precise combination of strength, hand and eye coordination, concentration, memory, patience and discipline.

Overcoming the unfavorable odds of being born Black, to a family of limited means, and raised in the segregated Deep South during the Great Depression, Aaron rose to become one of the most consequential figures in American history. Surviving those circumstances were as challenging as hitting a baseball. Born in 1934 in Mobile, Alabama, he learned to survive in a racially hostile environment where Blacks were uniformly denied the most basic of human and civil rights. Until he was 13 years old, when Jackie Robinson broke the color-line in baseball, his athletic talents could not have found expression beyond the Negro Leagues – a place where the unsung players were as good as those in the Major Leagues. Until that time, Aaron, as did most other Blacks, found hope in the athletic exploits of Joe Louis and Jesse Owens whose exploits demonstated the democracy of competition on level playing fields –something Blacks were denied in larger society.

Carter G. Woodson understood the dynamics and symbolism of this intersection of sports and society. He commissioned Edwin B. Henderson to research and write the seminal book, The Negro in Sports, published in 1939 by ASALH’s Associated Publishers. The Urban League, NAACP, and the scores upon scores of vibrant Black newspapers also appreciated the role of sports in the struggles for social justice. After short stints in the Negro Leagues and the minor leagues, Aaron’s debut with the Milwaukke Braves cames in 1954, one month before Brown v. Board of Education, though it would be years before the racial codes of conduct would be lifted and he would enjoy many of the same hotels, restaurants or be allowed to live in the same neighborhoods of his white teammates. He led the Braves to the World Series title in the fall of 1957 and was league MVP, the same season that Eisenhower deployed federal troops for the integration of Central High School in Little Rock , Arkansas. For the remainder of the 1950s, he continued to be an All-Star performer, but was reluctant to speak in public about social issues, mainly because of his insecurities resulting from his lack of formal schooling. At the same time, though, he identified strongly with civil rights causes, especially after hearing and reading James Baldwin. On his own, he continued to read, observe and grow. In the first half decade of the 1960s, he became transformed, and upset many who thought they knew him –owing to his quite, calm and dignified persona — when he wrote that ” regardless of who you are and how much money you make, you are still a Negro.”

From that point forward, Aaron used his celebrity to promote social justice and equal opportunity, while simultaneously having one great baseball season after another, ultimately leading to his induction into the Hall of Fame. Baseball is a game of records, and because the basic dimensions of the game have not changed over time, it allows for the comparison of players from one era to those of another. No single record , however, had the prestige as that of Babe Ruth’s 714 career homeruns. By 1973, that record was in sight for Aaron, and his chase of it came during tumultuous times. The unfolding Watergate scandal and the ending of the Vietnam War, the era of Muhammad Ali, Wounded Knee, Roe v. Wade, oil shortages, and a nation struggling with deep divisions were the backdrop. Aaron and major league baseball underestimated the bitterness and resentfulness that would ensue in his pursuit of that record. For two and a half years, a dignified, calm and stoic Aaron had to sustain the concentration necessary for hitting a baseball, while enduring the wrath of hate mail and bigots, death threats, the slights of baseball’s commissioner, the around the clock protection for himself and family, and his personal desire to break the record, for himself, his race and his sports fans.

On April 8, 1974, Aaron hit his 715th homerun. Broadcaster Vin Scully addressed the racial tension : “What a marvelous moment for baseball, what a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia; what a marvelous moment for the country and the world. A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol.” Aaron would go on to hit 755 non-drug enhanced homeruns, still a major league record.

Aaron, a life member of ASALH, would go on to be awarded with the NAACP Spingarn Medal; the Presidential Medal of Freedom ( Bush); the Presidential Citizens Medal ( Clinton), the NAACP Legal Defense Fund Thurgood Marshall Lifetime Achievement Award; and his Chasing the Dream Foundation has funded many scholarships and grants for college students, given millions of dollars to HBCUs, and sponsored scores of youth organizations. Aaron was generous in providing his brand identity in promoting numerous socially conscious and progressive organizations.

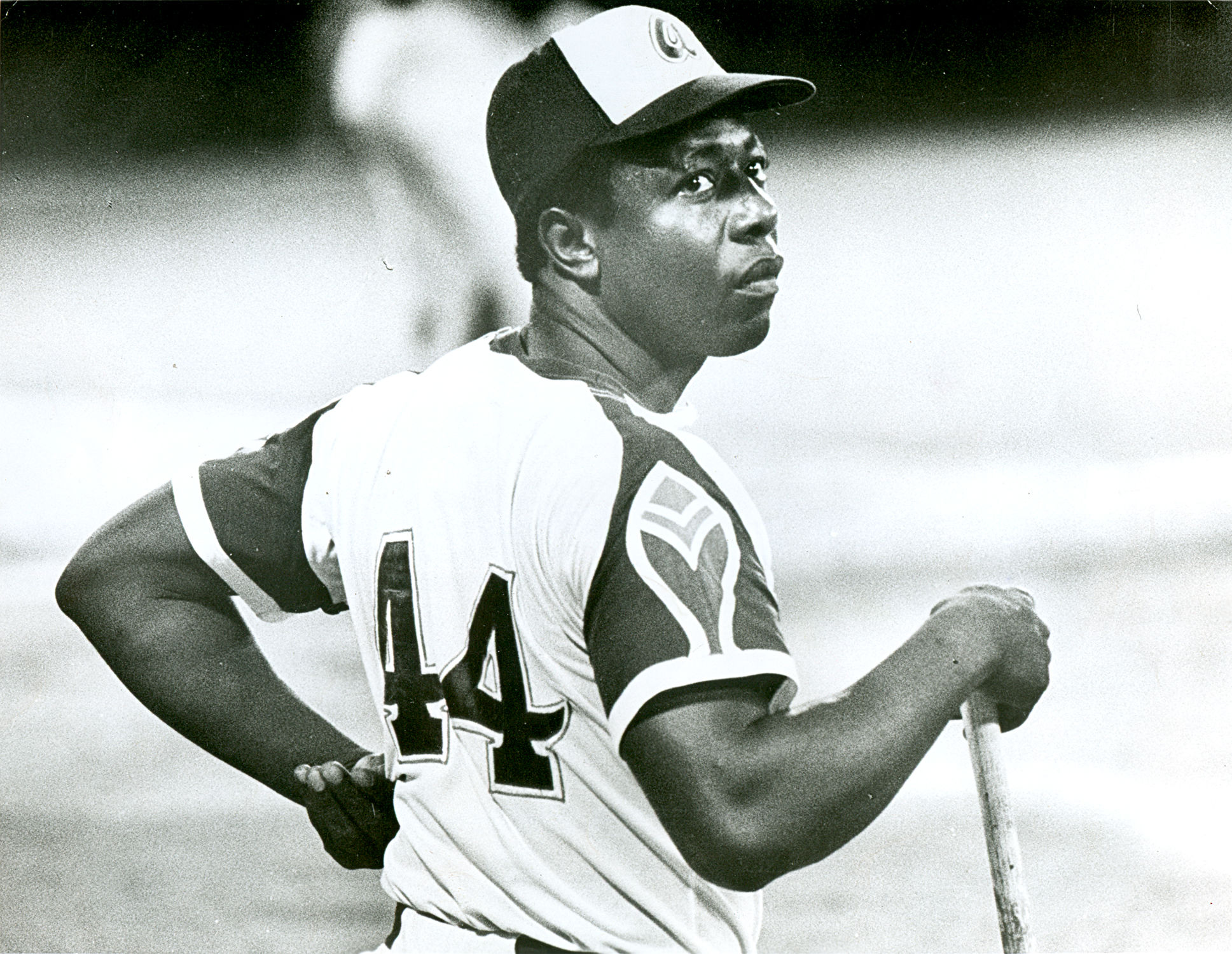

It is with deep gratitude that ASALH pays tribute to the inspiring life and legacy of Henry Aaron # 44, the number on his jersey, whose contributions through sports are no less than those of Barack Obama # 44 through politics. He was an unmatched lighthouse of grace and solemnity.

Al-Tony Gilmore, Distinguished Historian Emeritus, National Education Association, and ASALH Life Member.