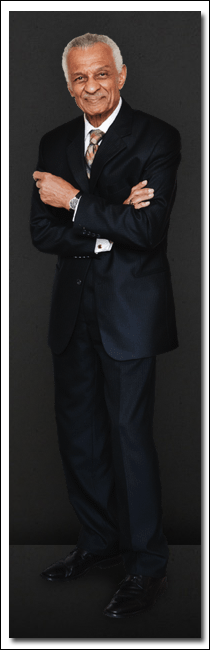

Tall trees are falling. The Rev. C.T. Vivian, a friend of ASALH has gone to be with the ancestors. I first met him in August 2011, at what was supposed to be the public unveiling of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. memorial in Washington (the unveiling was postponed because of Hurricane Irene). I found the Rev. Vivian standing tall and straight, speaking with U.S. Representative Bobby Scott and a few other prominent figures members of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. We were waiting to walk to the site where a monument of an American King stood between presidents.

Tall trees are falling. The Rev. C.T. Vivian, a friend of ASALH has gone to be with the ancestors. I first met him in August 2011, at what was supposed to be the public unveiling of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. memorial in Washington (the unveiling was postponed because of Hurricane Irene). I found the Rev. Vivian standing tall and straight, speaking with U.S. Representative Bobby Scott and a few other prominent figures members of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. We were waiting to walk to the site where a monument of an American King stood between presidents.

As was the case when I met another great Alpha man and ASALH stalwart, John Hope Franklin, I was not at all “ice cold” approaching the Rev. Vivian. Admittedly, I had no chill whatsoever. I awkwardly interrupted Representative Scott to tell the minister that he was C.T. Vivian. I said boldly that I teach him in class; he looked at me kindly and said: “how you gonna teach me, Brother?!!” I felt my lungs deflate because I meant to say that I teach about him in my classes on the Civil Rights Movement.

He was so gracious in understanding my rambling explanation; I even quoted some of the words he said about democracy when, in 1965, racist police denied his entrance into a courthouse in Selma to register Black voters (I had just showed the “Bridges to Freedom” episode of Eyes on the Prize Video in the previous spring). He asked where I taught, and I responded “St. Louis.” He then grabbed my arm (with a certain strength I did not expect) and told me that we must talk. The Rev. Vivian asked for and took my card and promised to call. I did not believe him.

Not more than three weeks later, I came to my office to find a cheery voicemail addressing me as “Doc,” and asking that I call him back immediately. It was the Rev. Vivian. Of course, I returned his call–after hi-fiving myself and staring at the picture of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. and his line brothers that hangs in my office. As I dialed, I felt guilty for ever having doubted the words of this Man of God. Bro. Vivian answered right away, and asked me about my work, and I told him I studied the entrance and activism of Black students in elite higher education institutions. He said, “ah yes I know something about that.”

Not more than three weeks later, I came to my office to find a cheery voicemail addressing me as “Doc,” and asking that I call him back immediately. It was the Rev. Vivian. Of course, I returned his call–after hi-fiving myself and staring at the picture of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. and his line brothers that hangs in my office. As I dialed, I felt guilty for ever having doubted the words of this Man of God. Bro. Vivian answered right away, and asked me about my work, and I told him I studied the entrance and activism of Black students in elite higher education institutions. He said, “ah yes I know something about that.”

It took me a while before I understood what he meant by he knew something about my research because he talked liberally and quite casually about how he and “Martin” or “Marty” and Jim (James Forman, James Bevel, and James Lawson at various times) and the others had to show those lawmen and other bigots the righteous way to go and get the people the vote. It was not braggadocio, but his tone was of a man who knew and conquered fear, who recognized he had the right to speak on history with an authority I may never have.

I loved every second of it. Some 45 minutes later, he said: “So, yes, St. Louis was the place that I helped put together a program to help Black kids get ready for college.” The Rev. Vivian explained that he, with a friend from the movement, and the man he called Jack Kennedy’s in-law [Sargent Shriver], had long and fruitful discussions that eventually led to a national pilot program after which Upward Bound was modeled. I stopped him and noted that he really did pave the way for the Black students who entered and transformed higher education, and, furthermore, made it possible for young people like me to succeed in college. I was stupefied.

As if standing up to and staring down an antidemocratic representative of American state violence like Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark was not enough, as if forcing the hand of the nation and especially the South to protect the right of Black people to vote was not sufficient, the Rev. Vivian changed the face of higher education as well. A part of what we now call Trio, Upward Bound rolled out in 1965 and made it possible for low income and first generation students, many of whom were Black, to attend colleges and universities throughout the nation.

Some of the students in the first cohorts of Upward Bound protested against racial injustices off and on their campuses when they arrived; additionally, they demonstrated against America’s participation in the increasingly unpopular war in Southeast Asia. Those students brought to predominantly white institutions their first Black administrators, professors, fraternities and sororities, Black Studies programs, and Black culture centers. They forced many of these universities and colleges to contend with their liberal missions in much the same way that the Rev. Vivian forced recalcitrant Americans to do so in his crusade for the vote.

On the telephone, the Rev. Vivian said there should be a record of his work somewhere in St. Louis and that I would be of great assistance to him if I could track it down. To my great shame and chagrin, I could not, and what is worse, I lost touch with the great freedom fighter. I meant to follow up, but life took hold.

From experience, I can testify that it is difficult to even muster the energy or courage to challenge institutional racism, and it is improbable to check the systemic discrimination that is so elemental to American society. The Rev. C.T. Vivian did so with class in both civic society and eventually in higher education. I have benefitted from his work in both realms. That is why I stand in solidarity with those who are challenging the abusive Sheriff Jim Clarks of today and those who are attempting to extirpate the voter suppression that is ravaging the democracy. I want to be like my dearly departed fraternity brother, the Rev. C.T. Vivian, who modeled courage, civic responsibility, and love for all mankind.

Stefan M. Bradley

Stefan M. Bradley

Professor, Department of African American Studies

BCLA Coordinator of Diversity and Inclusion Initiatives

Author of Upending the Ivory Tower: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Ivy League