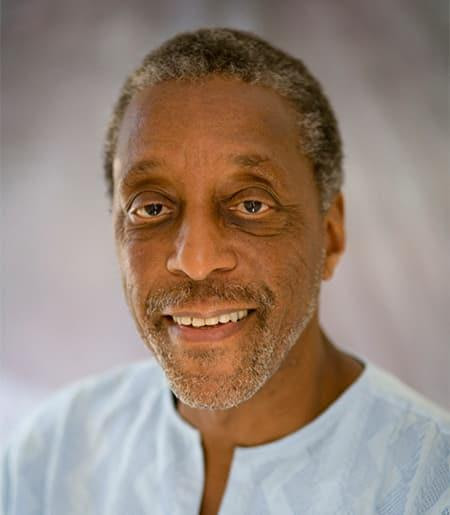

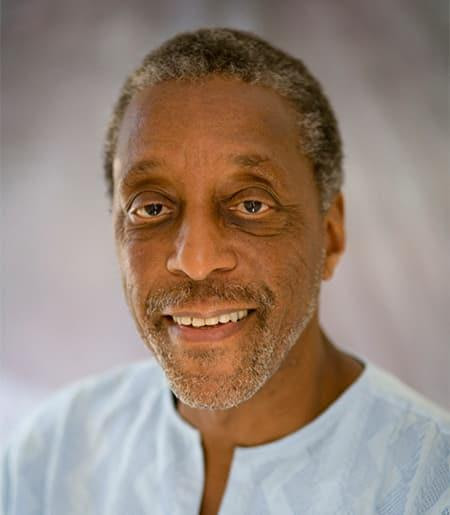

The Association for the Study of African American Life and History mourns the death of Dr. James Turner. Born in Brooklyn in 1940 and raised in Manhattan, he was a foundational leader in the making of Africana Studies (also known as Black or African American Studies), an academic discipline. His experiences growing up in New York’s Black public sphere exposed him to Black intellectual traditions born in local communities, rich with sources of knowledge and political inspiration. His parents, Willie and Frieda Turner had migrated to New York City from the Carolinas in the 1930s. In preparation for a career in the garment trades, Turner attended the High School of Fashion Industries and, after graduating in 1957, went on to work at Ripley’s Clothing Store.

The Association for the Study of African American Life and History mourns the death of Dr. James Turner. Born in Brooklyn in 1940 and raised in Manhattan, he was a foundational leader in the making of Africana Studies (also known as Black or African American Studies), an academic discipline. His experiences growing up in New York’s Black public sphere exposed him to Black intellectual traditions born in local communities, rich with sources of knowledge and political inspiration. His parents, Willie and Frieda Turner had migrated to New York City from the Carolinas in the 1930s. In preparation for a career in the garment trades, Turner attended the High School of Fashion Industries and, after graduating in 1957, went on to work at Ripley’s Clothing Store.Dr. Turner’s early political education, in large measure, sprang out of Harlem’s public sphere in the late 1950s and early 1960s, where he encountered seasoned veterans of the freedom struggle — such as Richard B. Moore, Carlos Cooks, and John Henrik Clarke — along with Malcolm X, Sonia Sanchez, Larry Neal, and Amiri Baraka and other younger activist and intellectual voices. Moore and Clarke were two of Turner’s Harlem-based mentors who encouraged him to study Black history and political thought.

Turner was frequently invited to Clarke’s home in Striver’s Row– where the historian regularly hosted scholars, literati, and activists. Turner was also inspired by Nation of Islam minister Malcolm X, of Harlem’s Temple Number 7, whose eye on the systemic causes of social crises in the Black community resonated with the beginnings of Turner’s activist and academic interests.

After leaving Ripley’s Clothing Store, Turner began working for the mobilization for a Youth program in 1961 at Columbia University’s School of Social Work, coding data on New York youth participation in gangs. There, in the academy, he explored urban sociological theories of youth delinquency among communities of color, which spoke to his own previous experiences as a member of the neighborhood gang or “street club” during his high school years, known as the Sportsmen. Under the pseudonym “Oren”—a reconfiguration of his nickname Reno—Turner’s insights on life in the gang were quoted in Harrison Salisbury’s book The Shook-Up Generation.

By 1962, while working as a researcher at Columbia, Turner began to consider the notion of attending college himself. Theory and practice also converged with a job he acquired at the New York Youth Board counseling gang members and working closely with local social workers. The position seemed ideal, but Turner soon discovered that he would eventually need a college degree to remain in the job on a full-time basis.

After a long-term courtship, James Turner married Janice Pinkney, who was already enrolled at City College while working at P.S. 122 Junior High School as a teaching assistant. The Turners explored the possibility of going away together to attend college. Though Jim Crow pushed them away from certain schools and even the South as a region, the Turners were drawn to another distinction mentioned in the institutional highlights of the Complete Guide—housing facilities for “married” students. After having been accepted to several schools that provided living quarters for families, they decided on Central Michigan University.

In the late summer of 1963, James and Janice Turner met with Malcolm X. They shared their plans. The minister generously arranged for his brother Philbert to pick the Turners up from the Greyhound bus depot in Lansing, Michigan, and host the couple at his home. At the same time, they awaited the transfer bus to arrive for the remainder of their trip to Mount Pleasant. James Turner moved quickly through Central Michigan’s BA program in Sociology and Political Economy, Janice Turner went on to complete a master’s degree in Counseling Psychology and Education. The two of them did so while raising a young son. On his way to graduating with honors, Turner was encouraged to consider graduate school. In 1966 he decided on Northwestern University given its fellowship resources, strong African Studies program, and archival holdings—especially the Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies. While in Evanston, Illinois, Janice Turner worked as the director of the local Head Start program. James Turner pursued a master’s in sociology focusing on social mobility and stratification and a certificate of specialization in African Studies.

Through organizing student agitation at Northwestern, James Turner gained national notoriety as a leader in the Black Studies movement. He presented at a five-day conference, “Toward a Black University,” held in November 1968 at Howard University. This gathering added to the development of shared leadership and curricular issues in the Black Studies movement. He networked with students from the Afro-American Society (AAS) at Cornell University who were fighting for Black Studies on their campus. Members of the AAS, advocated for him to become the director of Afro-American Studies while going through negotiations with the Cornell administration from the winter of 1968 through early 1969.

Once he began the position, Dr. Turner began the process of institutionalizing his vision for Black Studies, embracing “Africana” as a theoretical framework for a specific approach to Black Studies. Carter G. Woodson and W. E. B. DuBois evoked the term earlier in the twentieth century as a reference to the history and cultures of continental Africans and people of African ancestry around the world.38 In this spirit, Turner deployed “Africana” to emphasize the interconnections between and within multiple geographies and peoples throughout the Black world. The classes offered at the center have consistently reflected this expansive vision and in a broad range of fields, such as African American history, African languages, Caribbean politics, and African literature and art history. The Africana Studies and Research Center, born of student activism and Dr. Turner’s visionary leadership, thus became a place where interdisciplinary and transnational approaches to examining the Black experience stood as basic premises for its daily operations and pedagogies.

From Turner’s vantage point, the focus on relationships between African peoples worldwide incurred a responsibility of active participation in the international politics of Black liberation. Turner positioned the center as a resource to support nation-building efforts and liberation movements resisting colonialism and Apartheid. In keeping with this Africana vision, Turner accepted leadership roles in several political and cultural organizations: the African Heritage Studies Association, the African Liberation Support Committee, the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America, the International Congress of Africanists, the North American delegation to the Sixth Pan-African Congress, TransAfrica, and the Malcolm X

Commemoration Commission. While grappling with the day-to-day challenges of leading the center and institutionalizing Africana Studies during this early phase, Turner completed doctoral studies in 1975, at the Union Graduate School. His dissertation examined structural racism and Black Nationalism and anticipated a range of ideas explored further in his later publications.

On the local level in Ithaca, Dr. Turner positioned Africana Studies and Research Center functioned as a movement resource and incubator of activist values in cooperation with parallel institutions aimed at enhancing the quality of life for students and the Black community of Ithaca at large such as Wari House (a housing unit founded to establish a supportive environment for Black women students), Ujamaa Residential College (infusion of Africana Studies with student residential life), Committee on Special Education Projects (centered on recruitment and retention from diverse communities), and Southside Community Center.

The most enduring legacy of Dr. Turner is the work done by the many students he’s taught over the decades, who continue to actualize aspects of the Africana ideal in diverse and unique ways – as evidenced in a wide range of professions: grassroots community activism, scholarship, teaching, medicine, architecture, law, public service, engineering, social work, public education and beyond. Africana lives through the work Dr. Turner has inspired many to do, in service to our community.

This obituary was reprinted with the permission of Dr. Scott Brown. Dr. Scot Brown is an associate professor of African American Studies and History at the University of California, Los Angeles. Brown is the author of the book Fighting For Us, and has penned numerous articles on African American history, social/political movements, music and popular culture.